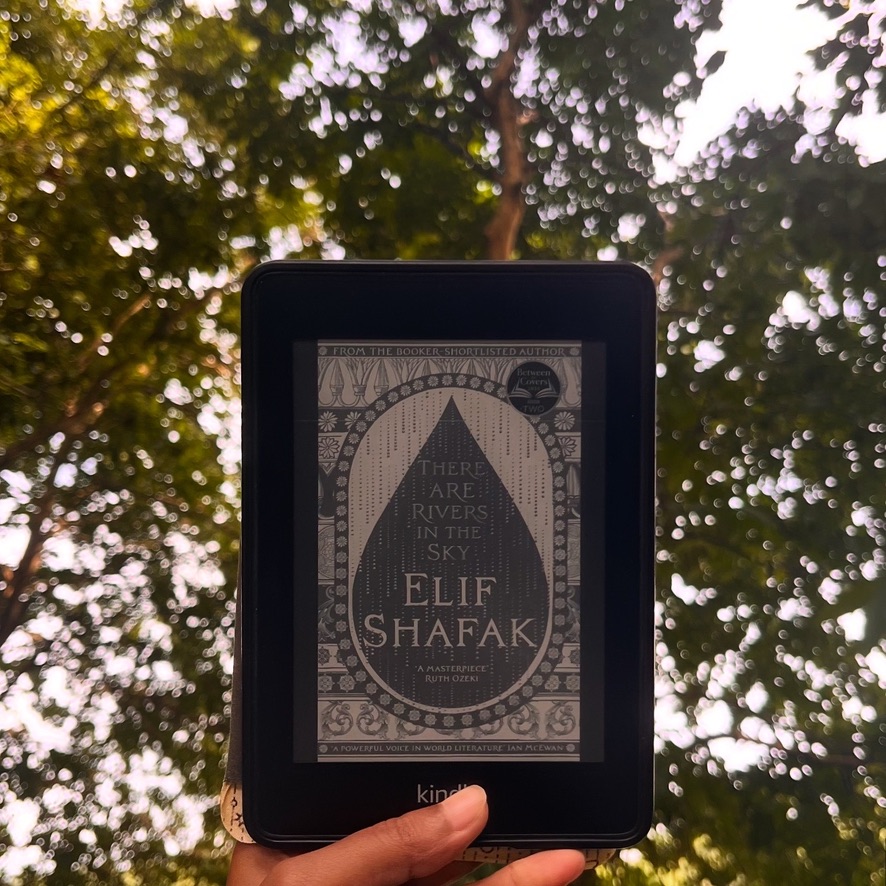

Book 7: There are Rivers in the Sky by Elif Shafak

Outside in the courtyard, the pine trees tower over him, silvery and needle-sharp, as if a giant seamstress has used the green hillside as her pincushion.

Shafak, Elif. There are Rivers in the Sky (p. 302). (Function). Kindle Edition.

Whenever I post about Elif Shafak, you should take what I say with a pinch of salt. I’ve been a huge fan of her for over a decade. As a fan, I have also criticised her for some writing that I thought was insipid, and some over-the-top romanticisation that she indulges in (which is no harm because we need that from time to time). For eg, some of her books after Honour, were not as enjoyable. It was also the time she had just moved to England and perhaps, was learning how to write in English first, rather than how she did it earlier in her career – write in Turkish and then translate to English. I say this as a disclaimer because it is very evident in this latest book how much she has grown as a writer.

There are Rivers in the Sky is one of the most well-researched books I’ve read this year. This, even after I read When We Cease to Understand the World which is non-fiction so its whole job is to be research-based. I’m telling you writers of fiction do it much better.

Alternating between three timelines, this is an ambitious novel. Set in London (1840 and 2018), and Iraq (by the river Tigris 2014), it takes us through the stories of Arthur (London), Narin (Iraq), and Zaleekah (London), who are somehow bound by a tale set in Nineveh, 640 BCE. Yes, ambitious. When I read the blurb and the scale of the book, I was dismayed because it takes extraordinary skill to pull off something of this scale. Suffice to say, except for tons of purple prose about water’s spirituality and chemistry, Elif Shafak has shown what good research can do to tell a good story.

Arthur is born in penury and grows up to become an archaeologist in London of 1940 where the River Thames is a breeding ground for diseases and filled with filth. Narin is a young, going-to-be-disabled Yazidi girl in 2014 who needs to travel to Valley of Lilish in Iraq for her baptism. Zaleekah is a scientist (hydrologist) in 2018 London whose subject of research is water and if it has memory. Water is the common thread that runs through the stories of these three charaters. Each of them trying to live as best they can, sometimes reaching for lives greater than the ones they’ve been given. All three of their lives intersect in a strange way, and the plausibility of it, does not seem as far fetched as it would.

For me, I enjoyed Narin’s chapters the most because I had never read enough about the Yazidis in story-form. Using her privilege as a Turkish Muslim woman, Elif has told the story of this Yazidi girl, her family, her village, her grandmother (obviously), and their religious beliefs, which is why they’re being persecuted by the Muslim majority, and ISIS. These chapters were beautiful, and terrifying; specially when Narin is captured by ISIS. A whole side of the Abrahamic faith, culture, and food habits opened up for me that I had no knowledge of hitherto. I would recommend just these portions even if you’re not inclined towards the rest of the book. News articles don’t humanise persecuted people, and I was very glad that this storyteller has done it. 5/5 for all of Narin’s chapters.

The purple prose across the book about the importance of water, rivers, and its role in the life of living beings had me groaning after a while. I wish the editor would have snipped out a lot of these lines. While they were needed, it seemed like there were too many of them for my liking.

Overall, this is a book full of good intentions, inclusivity, and so wide in its expanse reading it was a joy because there’s so much in it that I love – whether it is about the sanctity of rivers in a city, the wonder of old stories, folklore stories from different cultures, overcoming of obstacles based on the power of dreams, and a whole lot of love for the world we live in.

‘Remember, child, never look down upon anyone. You must treat everyone and everything with respect. We believe the earth is sacred. Don’t trample on it carelessly. Our people never get married in April, because that’s when the land is pregnant. You cannot dance and jump and stomp all over it. You have to treat it gently. Do not ever pollute the soil, the air or the river. That’s why I never spit on the ground. You shouldn’t do it either.’ ‘What if I have to cough?’ ‘Well, cough into a handkerchief and fold it away. The earth is not a receptacle for our waste matter.’

Grandma says an elderly Yazidi woman, a dear neighbour of hers, migrated with her children to Germany, where the family settled in the 1990s. The woman was puzzled and saddened when she learnt that people over there filled a bathtub with water and then sat in it to soap themselves. She could not believe that anyone would be senseless enough to plunge into clean water without having first washed themselves. Grandma says one should also pay homage to the sun and the moon, which are celestial siblings. Every morning at dawn she goes up to the roof to salute the first light, and when she prays she faces the sun. After dark she sends a prayer to the orb of night. One must always walk the earth with wonder, for it is full of miracles yet to be witnessed.

Shafak, Elif. There are Rivers in the Sky (pp. 180-181). (Function). Kindle Edition.

🌟 4.5/5

Leave a Reply